This is the third of three posts about death, of which the first was Death: when and who and the second was Death: how and why. It’s also a great chance to develop one of my favorite topics, ultrasociality, last mentioned in Get away from her, you naturalistic fallacy!

This is the third of three posts about death, of which the first was Death: when and who and the second was Death: how and why. It’s also a great chance to develop one of my favorite topics, ultrasociality, last mentioned in Get away from her, you naturalistic fallacy!

This bio joke’s so old it’s moldy, but unlike the topic of this post, it ain’t dead. An ecologist and a systematist are standing in a room when thousands of rubber balls are released from the ceiling, in a profusion of sizes and colors. They fall and bounce, and keep coming, a whole spectacular display of rubber balls in action. The scientists stare in fascination and delight. The ecologist exclaims, “Look at all the diversity!” The systematist exclaims, “Wow, 9.8 meters per second per second!”

My thinking tends toward the latter, especially when talking about humans and human culture as an animal phenomenon. Looking over the various nutbar things we do with and about human corpses, I see what’s the same about them all, and without discounting the diversity as “just” or “only,” that’s where my attention goes.

During my final couple of years as a prof, I designed and taught an interdisciplinary freshmen-only course called “Birth and death in Chicago.” It was a tough, deep subject and two reps weren’t enough to get it into the humming shape I want for a class. But it was a good start, and one benefit was discovering McCorkle’s excellent Ritualizing the Disposal of the Deceased. It’s one of the few examples of genuinely examining human practices from an evolutionary perspective and maintaining a rigorous relationship among theory, data collection, and argument.

He points out some things: corpse handling isn’t a straightforward, logistic problem based on public health policy; it’s expensive, highly loaded with family and societal conflicts, and ritualized in what appear to astonishingly arbitrary, even extreme ways. It seems tailor-made for saying, “gee, that’s culture” in that bio-shutdown way that’s unfortunately so common in academia. McCorkle’s presentation offers a way to start addressing that head-on.

Ultrasociality

This form of socializing is observed among some species who live in extremely dense clusters, and typically including those with complex kin behaviors (families). It’s a second-order shift in interacting with non-related individuals, such that complex alliances, recognition, reputation, and group-based identities are involved. The best way to look at it is that one’s involvement with groups (of which “status” or “position” is only one part) is so relevant to reproductive success that the conditions or permutations of one’s society are the most relevant environment, far more so than things like average temperature or rainfall or predators (although such things never become irrelevant).

Ultrasocial creatures conduct mate choice, mate competition, and parasite avoidance to an extreme degree out of sheer volume of personal contact, and they also recognize and communicate with one another constantly. All the “personal” details of life that affect reproductive success, such as mate choice, cease to be one-on-one decisions and are now enclosed in and suffused by the judgments of everyone else, which are also taken into account when making those decisions.

I stress that when I say “environment” I do not mean selective in terms of limiting or changing intrinsic parameters of human behavior at the local population level. I’m talking about conditions which affect which behaviors are most observed, or which historically provide idioms which are then continued as custom. Humans can do anything human. Geographic, historical, economic, and learning-developmental specifications result in different influences on how they act – although as I see it, a lot less different than most cultural anthropologists or sociologists would have it. It might also help to stress that ultrasociality is well-known across a variety of animals and there is no need to rely on insider-knowledge of being human in order to grasp its nuances. To the contrary; the primary insight comes from understanding it through comparative work and then discovering how well we conform – in our way, each species is indeed its own thing – to what we’ve seen and analyzed.

I also need to explain cognitive mapping, which is making up an imaginary universe in your head as a working model of the reality you live in. We do not really “use our eyes” – we parse what we see in terms of what the cognitive map holds, and changing the map via senses and experience is a lot harder than one might think. It’s really easy to pull tricks of compartmentalization and spurious differences in order to justify what one just saw or otherwise sensed such that the map remains intact, i.e., to stave off cognitive dissonance.

Like ultrasociality, cognition of this kind isn’t a special human thing. I tend to be very generous in how widely I think it’s distributed through Animalia – what’s different from species to species is a matter of what variables are those most observed, in what sensory range, and to what degree, and how they’re remembered, processed, and applied in decision-making. Our cognition is not special as such; it is, however, good at certain things and bad at others, just as with any species. Crucially, our major competence lies not in, for example, spatial memory or risk projection, but in soap opera. We are outstanding at remembering and adjusting an incredible web of who did what with whom, who said what about whom regarding those things, and who knows and doesn’t know what about whom, all with various degrees of certainty assigned to them, and with scary attention to manipulating those mental machinations in others. Like all cognitive maps, though, the relationship between sensory data and map content is murky and dangerous, in that “oh gee, I was wrong, I’ll adjust my map” is much harder than “gee, this person isn’t acting like I thought or was told, so he/she must be lying now, or disturbingly inconsistent.”

Like ultrasociality, cognition of this kind isn’t a special human thing. I tend to be very generous in how widely I think it’s distributed through Animalia – what’s different from species to species is a matter of what variables are those most observed, in what sensory range, and to what degree, and how they’re remembered, processed, and applied in decision-making. Our cognition is not special as such; it is, however, good at certain things and bad at others, just as with any species. Crucially, our major competence lies not in, for example, spatial memory or risk projection, but in soap opera. We are outstanding at remembering and adjusting an incredible web of who did what with whom, who said what about whom regarding those things, and who knows and doesn’t know what about whom, all with various degrees of certainty assigned to them, and with scary attention to manipulating those mental machinations in others. Like all cognitive maps, though, the relationship between sensory data and map content is murky and dangerous, in that “oh gee, I was wrong, I’ll adjust my map” is much harder than “gee, this person isn’t acting like I thought or was told, so he/she must be lying now, or disturbingly inconsistent.”

Consider too that although real people are animals moving in space, the cognitive map holds characters operating in stories. What are the operating features of these characters? McCorkle’s questionnaire-based profiles suggest two independent concepts of a human being’s presence.

The person-file, is the most familiar to me based on research on behavior. This is the held image of the person as a distinct personality, with kinship, a set of priorities, a raft of obligations in all directions, membership in groups and positions relative to other groups, a history of relationships and events pertaining to them, and all manner of other social variables.

The other one, agency, is most fascinating when you consider it’s independent of the person-file. We recognize agency in all sorts of things we do not consider people, no matter whether they do in fact fulfill certain behavioral criteria we like to pretend only people have, or whether they move. It’s what you recognize insofar as a thing can be said to do something. This is, too, how we Otherize real people, by considering them to hold impenetrable agency for which empathy does not apply.

A person in the cognitive map, then, has both a person-file and agency, and now that this person is dead, we have to cope with the cognitive map’s versions of these things. This is raw cognitive dissonance: the person-file is still in there as a social reality both as itself and as a relevant relationship with others, the body used to have agency so it still might, and most importantly, they are both – this word applies perfectly – embodied in this corpse. Therefore the corpse is the perfect instrument to resolve what will otherwise be intolerable cognitive dissonance.

McCorkle suggests also that hygiene or as he calls it hazard-avoidance, is the least important consideration regarding corpse handling and disposal, about which more in a moment.

Ritual and religion

McCorkle investigates at length the prospect that rituals are not themselves invented and perpetuated by religions, but rather that the religions adopt what the people do – and when the two differ, the rites are usually carried out anyway, in tandem with the doctrinal instruction, as people blithely claim that these acts are part of the doctrine when they’re patently not. Therefore I’ll talk about religious layerings onto ritual practices after working on the former.

McCorkle investigates at length the prospect that rituals are not themselves invented and perpetuated by religions, but rather that the religions adopt what the people do – and when the two differ, the rites are usually carried out anyway, in tandem with the doctrinal instruction, as people blithely claim that these acts are part of the doctrine when they’re patently not. Therefore I’ll talk about religious layerings onto ritual practices after working on the former.

McCorkle’s view, which I share, is that representation is misnamed – the symbolic object or color or whatever is completely arbitrary. This view is the opposite of Otherizing unfamiliar practices as intrinsically exotic, also called, as named after a common example, orientalism. Instead, he, I, and others suggest that no human practice is exotic. Even if simplistic generalization that “in the west, the color of death is black, but in the east, it’s white,” were true, the visual difference doesn’t indicate a different attitude toward death.

Similarly, rituals don’t actually do anything to their ostensible subject, but they apparently do something for us when we conduct them. Representations and the rituals which enact, dramatize, and reassign them, are connected within the mind and across public space. In other words, this is our means of rolling up our sleeves and however carefully and with a great deal of “knowing what to do when because otherwise disaster,” tinkering directly with the cognitive map and knowing that everyone around you is doing the same. A ritual is a way for everyone to say, either remember we do it this way in case anyone was wondering, or, and more relevant for the present topic, now we are agreeing to think about this particular ‘unit’ differently.

Anyway, in a nutshell: one of the primary and highly-prioritized behaviors that these rituals maximize, even dramatize, among all the participants is to shift the person-file into, if you will, the mental morgue drawer. To “say goodbye” at the social and community level, so that the deceased person’s status in the community is now relegated into that category, and our expectations or obligations regarding him or her are now treated differently.

The thing that strikes me with every ritual and particularly the “farewell to the dead” is the attention to narrative. How is this event of death for this person going to be understood as an emotional story, with an ending that proceeds from the events of living and yet has thematic power, to be repeated among the community? Here is the origin of such phrases such as “meant to happen this way,” “better off now really,” “it was his time,” “he was ready,” and when it comes to people we don’t like and/or killed, “deserved it,” “had to go,” “going to hell.” I suppose one might also think in terms of including the cosmos in one’s community judgment, in that (for example) when he had his heart attack or was hit by the bus, was “meant to be” and somehow the event is justified or approved of at a level for which our community is deemed a small part.

Isn’t this “just” religion? I will slightly anticipate later posts by saying that the word “religion” on its own is not useful. I distinguish among observance, community identity, institution (particularly its educational branch, doctrine), and culture, especially as orthogonal variables rather than nested/reductive ones. I also think the word “belief” almost entirely vanishes when those variables are understood, and is in no way the core or root of religious practices.

In this case, I’m interested in religion as community identity. As McCorkle points out, religion as institution, as doctrine thereof, and as observance have to suck it up and permit or adopt the body disposal practices that are going on and will be going on – a church needs to adopt those practices to be valid in the community, rather than the other way ’round. Therefore clothing body disposal in a given religion and thereby tying it to other things like marriage, economic planning, and doctrinal education, is very common, but not definitional.

Technology

Hygiene isn’t entirely irrelevant, to be sure. Decay is literally the consumption of tissue by bacteria, with the various smells being what the little critters give off, and bacteria in that kind of volume are a definite health hazard to the living. Therefore body disposal is an understandable personal and civic task, and in communities of human size, it becomes a policy issue. Still: a body is not more dangerous in health hazard terms than the equivalent volume of any organic trash, such as we routinely tolerate in publicly-present bins for a few days. The widespread notion that bodies represent extreme health risks and continue to do so long after burial (for instance) is simply inaccurate. Bagged and binned, perhaps with a bit of lime, bodies could be removed twice weekly by trash collectors and handled just like the rest of such stuff with no public consequence.

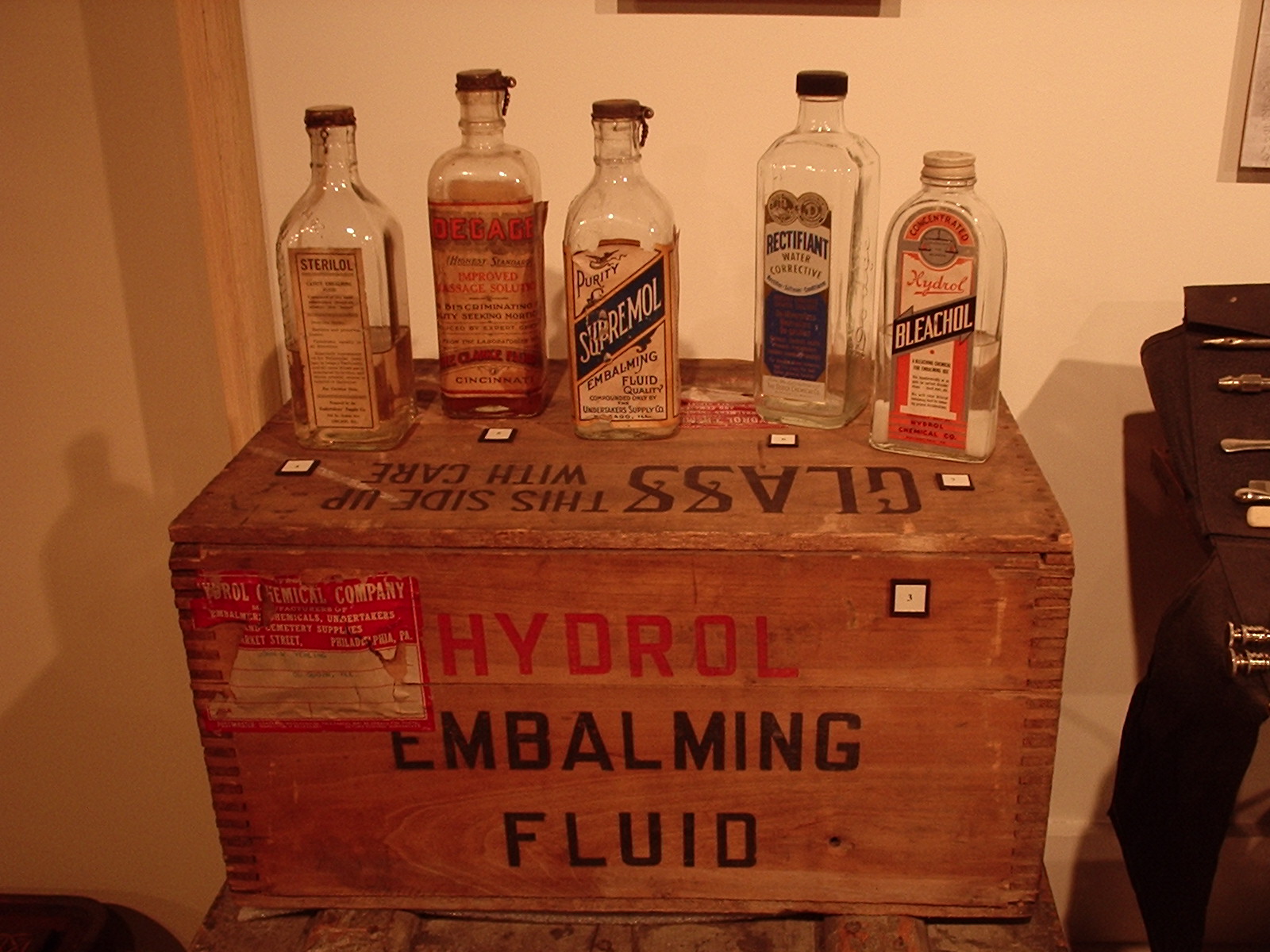

McCorkle suggests or at least strongly implies that the elaborate technology we bring to corpse disposal has a lot to do with removing its former agency. Now that we have reassigned or or are working on reassigning the person-file into “really gone” status, we also have this thing that used to move around and do stuff. Shorn of its person-file, that agency is a variable of its own, and scary.

Therefore the detail that catches my eye about the disposal is its finality, what in the world of animal welfare we call assurance. Making sure that if the critter isn’t dead based on your killing method, then it certainly is now. You could think of it nicely in that we don’t want to inter or otherwise dispose of a person who’s really still alive, but also less nicely in that now that we’ve decided the person is dead, we’re going to confirm that judgment absolutely even if he or she is still alive.

You can see my “9.8 m/s/s” in action here. I don’t see the diversity of burial with or without embalming, different forms of interment and entombment, “burial” at sea or as some have done in space (!), so-called “sky burial” (exposure for consumption by scavengers), cremation or some combination of cremation and burial, acidic dissolution or so-called “aquamation,” the grossly-misnamed cryogenics, and who knows what-else someone is going to spend money on tomorrow. I see, biochemically, the same thing every time regardless of the route or location, and ultrasocially, we’re talking about goodbye to the person(-file) and destruction of the potentially scary agency. This is why, regarding the body, both maximum preservation (in very unliving form) and maximum obliteration are both the same behavior. Keeping some pieces around such as parts or ashes or whatever seems like a neat blend of the same two concerns too. (icky thought: that hands are widely considered sinister in this regard, i.e., the one part of the human body most associated with distinctive and varying agency)

Elaboration and negotiation

I’m trying to respect his memory! / This isn’t what he would have wanted!

Now might be good time for a little home truth … I can just hear you out there: When I go, I don’t want anything elaborate, just bury me somewhere / burn me up, maybe have a little party, and move on. Sounds good to me too – except, guess what? It won’t be up to you. Or me. Or anyone who’s dead. That’s the one person whose wishes in this matter aren’t enforceable, and probably won’t be, especially if they concern being simpler rather than more complicated.

Ultrasocial beings have a lot of priorities to meet and negotiate about when doing rituals. One is tied to affirming community identity: “the way we do it,” and no surprise that this usually gets tied to religious institutional authority. Another concerns one’s own person-file, sort of “if these people and I do it for him, then I know they’ll do it for me.” Yet another is solid conspicuous consumption, what biologists call stotting after a particular dramatic version in ungulates, and which in people includes the blatant expenditure of items and wealth-resources in addition to bodily reserves.

What then comes into conflict, or might, is the person-file of the deceased in, say, his or her best friend’s head, vs. the ones in his or her parents’, vs. the ones in the heads of the people who feel strongly about how “we” do funerals “around here” and who exert social authority about it. Resolutions quickly arrive in terms of social power among the living rather than on the sincerity or accuracy of the various person-files about that person.

There’s also the consideration of intra-kin conflict, something that deserves its own post, and in this case is best understood as battling to control the person-file narrative. All of us are, for lack of a better word, a bit bonkers when it comes to the significance of family interactions, and our long maturation period, extensively overlapping generations, and extremely high cost in offspring terms exacerbate our obsession with what our family members think and who can tell whom what to do. Confounding resources variables like money and property doesn’t help either. In figuring out how the rituals of a given body disposal – specifically the person-file aspect – will be conducted, it’s practically axiomatic that these tensions are going to be brought into the open, and that standing disagreements will escalate. For example, and to be a little daytime TV about it, how does the deceased’s recent and much younger spouse figure into this relative to his or her grown children? Try that one with disputes not only about inheritance but about who gets to talk and who standsd next to whom at the funeral service, and you can bet each individual person-file of the deceased, in each person’s head, is going to be invoked as a participant in the ensuing discussion.

Thus: when each of us has died, or let’s be blunt, when I die, “I” will be gone as a biological phenomenon. But in everyone’s minds, I’m not socially gone until they … well, until they get rid of me.

Recommended: the single best book on ultrasociality, Richard Alexander’s The Biology of Moral Systems

Next: Have you ever really looked at your hands?

Maybe it’s the encroaching holidays (combined with my own continuing, utterly normal – while also particularly personal – aging process, er, that is, my own progress towards death). But what I’m left with here is a personal sense of persistence to the agency of those now dead or long unheard-from. Admitting that it’s hard to know if I’m “noticing” or “inventing” things like “wow, my sister is acting just like our grandmother used to regarding x” or “huh, there are bits of ‘child of the Depression’ (which I most certainly am not) in my reluctance to throw stuff away”, I’m still left thinking that socially, they DON’T get rid of you easily. Nor do I get rid of them easily. I mean, they-hundreds-of-years-from-now will be pretty well rid of me, but short-term, destruction of agency seems way less than absolute. And undesirable, at least in some particulars.

LikeLike

I agree. I do however see a boundary established. The part that gets removed is a person’s demand on others, and how much, and about what, is a matter of some weight among the living. The expectation of the social ritual, I think, includes a hefty amount of this … obligation, caring, consideration … no longer being a community concern. At the individual level, it varies more, but again, there’s an extent that the community isn’t going to honor no matter how much one person still feels it. Cherishing a beloved memory is one thing; being haunted is another. I’m especially interested that the latter sensation or condition is understandable in the complete absence of an ectoplasmic or otherwise metaphysical entity.

LikeLike

I think I’m with you. Maybe I’d emphasize a bit that the balance between (or is it spectrum across?) “haunted” and “cherishing” is complex, but I have been (self-mockery ON) accused of over-complicating things (self-mockery OFF) .

I’d have thought that persistence of community concern would also be pretty varied, as I have a vague (i.e., not rigorously examined) sense that pretty extreme “venerate the ancestors” cultures do exist. Not that such a thing refutes your “9.8 m/s/s” regarding bodies, nor the universality to the importance of the rituals…

Now I’m left thinking about a whole community stuck in the “haunted” mode. Yikes!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Some good comments and Q&A in the G+ feed for this post.

LikeLike

One trivial thought about this (and I know I’m SUPER late in responding to it)….

Consider friends you’ve had, who you’ve drifted away from, or who have become estranged. You know you no longer have any kind of accurate read on their personality; nevertheless, there they go (or so you hear from third parties), running around getting married or having kids, exercising agency all over the place, just in ways you might not expect.

It may be this is what makes the 20th High School Reunion such a staple in American pop culture: it’s a weird moment in time where a person’s agency, exercised over 20 years, has reshaped the individual’s personality into something different-but-descended-from whatever that personality was at age 18.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m afraid I don’t understand agency as it relates to (or rather: is independet from) person-files. When we assign agency, do you mean stuff like “The weather’s going to totally spoil my barbecue tonight”, where we *resent* the weather for its effect on our plans? But, if that’s right, why is that not part of the person-files we keep for people? A colleague is undermining me at work, a policeman is giving me a break etc. — do these things not bleed over into the person-file, as a record of personaltiy traits and priorities which give us a clue regarding probable future behaviour?

LikeLike

Most of that kind of assignment are person-file, just as you say – with the proviso that I’m using the notion I’ve extracted or figured from McCorkle’s book, merely as a reader; I don’t claim expertise with the terms. I should explain that a bit more.

I mean, if someone had just defined these things for me outright, I’d have speculated that person-file was agency + empathy, or that agency was person-file – empathy. But that’s how McCorkle’s data becomes most intriguing, in showing (I mean, as a study, “best explained as”) independence between them, rather than one being part or a subset of the other.

So rather than arguing from definition, I’m taking that observation, or interpretation of his data, as read. And yes, I agree with you, it instantly raises the question of what is agency, in our minds, psychologically speaking? What does it look like when we assign it without person-file assignment at all?

I was thinking about your bug question in the other thread. I completely agree that we can, but let’s talk about the times when we don’t. Best example in my mind is when a roach scuttles out unexpectedly. Especially to a non-biologist for whom the word “animal” pretty much means mammal or anything reasonably cute. It’s not only a minor health hazard (or indication thereof), it’s not a creature with its own reality and history and personal interests. It’s … thing-ness, a scuttling horror, a bit of completely and unwanted activity that upsets all the order and activity that one is prepared to empathize with. Its agency, the things it doing, are (apparently) by definition impossible to think of as anything like one’s own, but are nonetheless present.

I was also thinking of the sudden motion made by … well, two things. A bit of landscape that I’d previously considered immobile, and the sensation I apparently have before recognizing it as an animal or understandable physical event. And a movement made by a dead body due to the motion of gases or a tilt or sudden muscle contraction, and how there is no cognitive response I know of involving my thinking it’s alive, but rather that it’s moving although it’s not alive.

But that brings me into the realm of saying, “how do I feel when I think this,” which is a generally a dangerous, self-fulfilling kind of analysis, so that’s as far as I’ll go with it.

LikeLike

Nice example — I, too, find it peculiarly disconcerting when a part of my surroundings moves without me being able to immediately ascribe this to a cause.

I’m still grappling with agency but I appreciate your answers. I guess I’ll have to do some further reading myself — which has been very rewarding when I read up on ultrasociality after reading this post, by the way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your analysis of the need to decommission the person now dead makes me think of the ways Neolithic and Mesolithic peoples disjointed the bones of their dead, cut them, buried and exhumed them again, and finally buried them somewhere else, sometimes in a distant common grave near megaliths and other sites that seem to have marked the boundary between the world of the living and that of the dead. What you propose makes sense of such rituals.

Those early people’s also engaged in “destructive” rituals when “decommissioning” houses or other buildings. They often burned down the structure and carefully sealed in the talismans (burnt bones, polished rocks) that had been placed in post holes as part of the ritual of building in the first place. Only then did they abandon a building or rebuild it. Clearly buildings had a presence analogous to that of family and kinfolk, though probably to a lesser degree. Both had to be ritually transferred to the place of the dead.

Having myself been overcome with powerful emotion when I visited my grandparents’ house many years after it had been sold out of the family, I have an inkling of the power that buildings can hold.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve been struck by how much modern behavior isn’t different. Your description of the dismembering, exhumation, and reburial exactly matches a personal story I encountered recently, and transferring whole cemeteries from place to place happens a fair amount. We tend to dress it up with arguments of necessity of one kind or another, but I don’t think that’s very important. What matters to me is when “the dam will flood the valley” happens, the coommunity or policy response is, “well, we better move the graves.”

Can you provide a link or reference for the buildings? As this is the internet, I clarify that I’m not throwing that out as defiance or implied refutation, but asking because I’m interested and want to follow up.

LikeLike

Pingback: Can biology accurately describe life and death? | OUPBlog