Stop now if you have to. I am going to discuss lap dancing. This is an in-depth look at a study concerning estrous cycling, the Pill, and tipping. Contrary to expectations, I’m not choosing it because the subject’s titillating or risque, nor to recoil in shock at the use of blinded technique on human subjects. I present it to demonstrate excellent scientific thinking, rigorous experimental design, and for once, a remarkably good understanding of how to examine human behavior.

Stop now if you have to. I am going to discuss lap dancing. This is an in-depth look at a study concerning estrous cycling, the Pill, and tipping. Contrary to expectations, I’m not choosing it because the subject’s titillating or risque, nor to recoil in shock at the use of blinded technique on human subjects. I present it to demonstrate excellent scientific thinking, rigorous experimental design, and for once, a remarkably good understanding of how to examine human behavior.

Oooh, and I’m also gonna gab about statistics – I figure, if the lap dancing and/or mention of sociobiology didn’t send you running off, that will set you jumping out the window and screaming into the night.

Here’s the full text: Ovulatory cycle effects on tip earning by lap dancers: economic evidence for human estrous.

This is a spiffy scientific diagram I scrawl all over the place when I teach statistical methods.

- The question at hand

- The hypothesis

- Methods

- Results

- Conclusion

- The hypothesis

- Implications

I’ve arranged it hierarchically with some care, using bullet points’ levels: the medium category (hypothesis + conclusion) is contained within the larger category of (question + implications), and it contains the smallest (methods + results) category.

Each level, with its paired terms, needs some attention.

- The question: how is human behavior affected by reproductive physiology? in what evolutionary context? do human women even display estrus?

- Implications

It suddenly occurs to me that I better provide the standard definitions to keep us from getting weird.

- Estrous cycle: The timed profile of estrogens and progesterone levels, associated with development and release of ova, in vertebrates; it’s subject to negative feedback between the brain and gonads, hence “cycle”

- Estrus: The distinctive appearance of or increase in proceptive behavior during the fertile phase (or potentially fertile) of the estrous cycle; colloquially, “in heat” – uh, “proceptive behavior” is a really polite way to put it

[Annnnd, the English language betrays us all again, because the British version spells the second term with an “-ous,” hence the title of the paper; and the second term has been known to arrive with a leading “o-” as well. Arrrghh!]

I’m never going to get along with philosophers of science. I don’t like positivism or its purported successor, critical rationalism. I think science has nothing to do with “constructing facts” and “finding truth” – it’s the debate and discussion of relevant and plausible things in the real world, in full knowledge that we’re in it too. This level of (questions + implication) is never expected to approach or be “true knowledge.” It is a discussion and although we do add implications after wading in reality, it never stops being one. (see my It is so difficult to think clearly for more about that)

It is genuinely interesting to consider whether and how human women are attracted to men, and how this attraction or advertisement thereof is conveyed, relative to their fertility. For one thing, our species is a bit unusual, although not unique, in having an all-year-long reproductive season, and similarly, unusual but not unique in that women are proceptive outside of that fertility phase. Is human female proceptivity entirely divorced from the hormonal cycle? More broadly, since obviously attraction and arousal are culturally constructed, are they only culturally constructed, or is there a chassis upon which that occurs?

It is genuinely interesting to consider whether and how human women are attracted to men, and how this attraction or advertisement thereof is conveyed, relative to their fertility. For one thing, our species is a bit unusual, although not unique, in having an all-year-long reproductive season, and similarly, unusual but not unique in that women are proceptive outside of that fertility phase. Is human female proceptivity entirely divorced from the hormonal cycle? More broadly, since obviously attraction and arousal are culturally constructed, are they only culturally constructed, or is there a chassis upon which that occurs?

Now let’s hop inside and see what to do in order to acquire raw material, to refine it, all toward the end of adding implications to the discussion. That’s what the subordinate hypothesis level is for. Clearly, it is not the entire question or questions – it can’t be, and will never be. It is a special case study that isolates a real-world situation in which the topic under discussion is expected to be occurring in some way.

That’s also why it’s not “what you’re trying to find out,” and not “what you’re trying to prove.” All of that is despicable gabble. We’re only discussing what might be physically actually happening. The hypothesis is a proposed causal agent which is plausibly relevant to the question. At its best it should include both the cause, the direction of proposed effect if any, and the target variable, i.e., the indicator or marker for the proposed effect.

- Q

- Hypothesis: women using the Pill receive less tips; AND, women using the Pill do not receive less tips

- Conclusion: (this will be one of the above statements)

- Hypothesis: women using the Pill receive less tips; AND, women using the Pill do not receive less tips

- I

Like Janus, it has two faces, (badly) named the alternate and the null. The alternate states the cause as if it really happened, in terms of how it would affect a named variable, and the null states the alternate as a negative – basically, “does not!”

The null does not say “this thing does not happen.” What it says is that anything else, outside the proposed causal agent, is or are the causal agent(s) in this situation. It represents, if you will, the entire universe of possibility that the proposed causal agent isn’t of distinctive interest in this case. The “controlled” aspect of the experiment is to render the proposed causal agent present in one group, and absent in another. That is why the null is 100 times more important than the alternative, because the alternative is always and ever, the one thing the null does not cover. It’s also why “null” is not defined as “nothing happens, no change.”

See, too, that the hypothesis is stated in the present tense? That’s because it does not concern the soon-to-be-conducted experiment. You do not hypothesize regarding what happens at your lab table; you hypothesize concerning the world as it is. The hypothesis, and its partner the conclusion, “look upward” to the larger category of (question + implications), and in no other direction.

What goes on inside the most-deeply nested category determines which way the conclusion swings.

- Q

- H

- Methods: experimental/control groups defined by women using vs. not using Pill; timed intervals defined by phases of the estrous cycle; response variable is monetary value of tips – note that neither the women nor the men are informed regarding the grouping or analysis

- Results

- C

- H

- I

Method sections aren’t exactly scintillating reading, so I’ll highlight a couple important points only. The women responded to a networking and email-based outreach, and participated via a website, therefore with no contact with the researchers. The information concerning tip earnings and estrous cycle was included in the recruitment process, but not their connection with one another, and in the midst of much other demographic information, therefore the study is reasonably considered blinded. A few days were deliberately dropped between menstrual-fertile and fertile-luteal for justifiable reasons regarding variability in actual fertility, and thus to keep the compared phases fully distinct from one another.

I like to mention too that this study presents a perfectly good example of “experimenting on humans” with no violation of ethics at all. Objections to it are easily identified as either offense that people lap dance and other people pay for it (and that the science somehow “legitimizes” it), or recoil from looking at humans through an evolutionary and non-medical physiological lens at all.

Aside from these, the only thing to know is that the 18 women reported their menstrual cycles and tip earnings. The rest is simply climbing back up the ladder all the way to the question-implications level, i.e., two jumps, one up from results to conclusion, and the next up from conclusion to implications.

- Q

- H

- M

- Results: significant positive difference in tips between Pill/non-Pill only during fertility phase

- Conclusion: (see hypothesis) either they do, or they don’t ; and they do

- H

- Implications: women may well display behavioral estrus, consistent with the notion that arousal indirectly promotes conception, and strengthening the general concept that some ordinary and cultural human behavior is “encased” or “founded” in reproductive physiology

Each upward jump is an inference. An acknowledged inference, meaning, yes, we know the dancers aren’t “all women” or even “all lap dancers,” and yes, we know that the conclusion, however well supported by data, is always possibly entirely wrong in terms of the whole big actual world/universe.

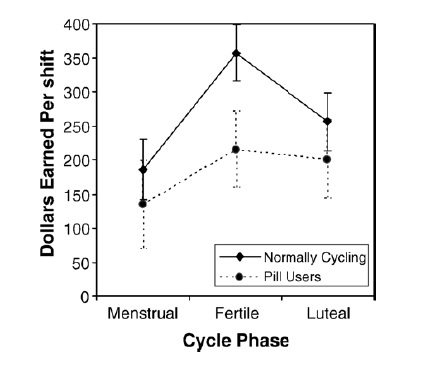

The hammer-strike of the results arrives in their Figure 2:

Let’s do some easy statistics now. The vertical lines associated with each dot are each mean value’s standard error, derived from its 95% confidence interval. The S.E. is nothing less than the range of possible real means that this data set is able to justify as being real – with an acknowledged 5% range of being dead wrong about that. The sample mean itself, bold and big as it is presented, is actually small potatoes in comparison to that range, intellectually speaking. Each range is actually fairly wide (or in the graph, tall) which is understandable considering the small (although not tiny) sample sizes.

Let’s do some easy statistics now. The vertical lines associated with each dot are each mean value’s standard error, derived from its 95% confidence interval. The S.E. is nothing less than the range of possible real means that this data set is able to justify as being real – with an acknowledged 5% range of being dead wrong about that. The sample mean itself, bold and big as it is presented, is actually small potatoes in comparison to that range, intellectually speaking. Each range is actually fairly wide (or in the graph, tall) which is understandable considering the small (although not tiny) sample sizes.

Let’s do the whole graph in plain language.

- Horizontally, phase to phase, check out whether the error bars overlap from phase to phase, per group.

- The graph says that the fertile phase is distinguishable from the other phases for the women who aren’t using the Pill, but that it is not distinguishable from the other phases for the women who are.

- Vertically, check out the overlap between the two groups’ error bars, per phase.

- The graph says that the menstrual and luteal phases are indistinguishable between Pill-using and non-Pill-using women, but that the fertile phases are indeed distinguishable between the two.

You can always state a figure in ordinary language. In fact, doing so is a standard question in my statistics tests. It’s also key to understanding a scientific paper – if you can treat it as a comic book and explain the chain of thought sequentially from figure to figure (including any graphic or table), then you may be said to understand it.

I love this stuff.

I made such a big deal about standard error because I’m not talking about the women in the study, but any-and-all women for whom they can reasonably be considered representatives. I’m already looking up to the conclusions level, getting ready to say something there. This is also where the technical term significant arrives, as part of results, deep inside this structure. Specifically, that the non-overlapping error bars for the fertile phase between the two groups of women are compared with a test of its own, yielding a p-value less than 0.01.

That value has a name: error. It’s a good thing but a terrible word for it – I think it’s better to say honesty, or reasonable doubt. It is never non-zero, and never, ever trivial or beyond reasonable doubt. Remember, the null hypothesis didn’t state some stupid or implausible different cause from the alternate; it merely stated the alternate is not the case. If we didn’t doubt the alternate-hypothesis statement in the first place, we wouldn’t be conducting the test at all. (Students always think error means “mistake” like when your labmate spills stuff, and that no procedural mistakes means no error. That’s a big conceptual problem that all stats classes need to get to killing.)

Anyway, saying “significant” regarding that non-overlap in the results allows us to hop up to the conclusion level, where we have one single thing to do: to reject the null / do not reject the null. Big golden thumb rule is, significance means, reject the null.

Wow. That’s a whole lotta universe to reject. It’s like we had this one little possible causal agent surrounded by any and everything singly or in combination that could be influencing this situation, and saying, yeah, screw all that other stuff, it looks like this causal agent actually does a thing here.

So that’s what goes up to the implications level. Yeah, there are lot of interrelated questions about human sexuality, attraction, arousal, commerce, and technically, estrous. Now, in discussing these, we need to take into account this particular case study, and can’t ignore the implications it has brought.

Miller and the co-authors show great and admirable care regarding the possible mechanisms that might be involved in their conclusion, specifically that they were not being investigated. We have no idea whether the fertile women were more aroused than the women using the Pill and therefore “gave a better show,” or whether the two groups of women gave essentially identical shows but the fertile women were stinkier in an arousing way, or what. Therefore the paper states outright, “we don’t know any of this,” because that’s not what was measured or tested. This is a coarse-grained study in many ways – the marker variable was money that changed hands, and that’s it.

I also appreciate the plain decency the authors display regarding the activity and the people who are doing it. At no point are the women described in a demeaning or humorous way. The lap dancing itself is described clinically but without concealing jargon. It’s flatly acknowledged as a real-world thing that goes on without a need either to pathologize it or giggle about it.

Too, the paper shows a complete lack of unjustified, obnoxious quacking: no “what women really want,” no “guys do this and girls do that,” none of the stupidity which is both committed by some self-styled sociobiologists and routinely assigned to sociobiology by its fearful critics. This is what it’s supposed to look like. The question is real and genuinely interesting. The specifications of the hypothesis satisfy prior plausibility. The design is sound, including the analysis and the phrasing of the conclusion. The conclusions themselves are properly positioned as contributions to the larger discussion.

Good science is founded on the intellectual integrity to make sense about how the world might work, to identify the idea’s relevance to some real-and-actual thing humans do, and to analyze that relevance in full acknowledgment that our means are subject to deep-set limitations. I also submit that it dares – dares to ask, for example, who are we, as real beings, doing the things we really do.

Next: Color coding

“This study has several limitations. The sample size of participants is small (N=18), although we gathered many data points per participant, which allowed us to use a statistically powerful repeated-measures design (including 296 work shifts reflecting about 5300 lap dances). Although the modest number of participants does not increase type I errors (i.e., false positives) in our statistical tests, it may reduce the generalizability of the results across populations”

Even in the understated world of scientific papers, the word “may” in that last line does a whole lot of work. I need to dust off my stats knowledge (I’m 20 years rusty), but I’m frankly baffled how you can report anything of statistical significance based on 18 people, and the 95% confidence intervals are absolutely enormous.

I mean: it sounds like an interesting experimental design that suggests a provocative (ahem) result difficult to directly measure, and thus it’s not wasted work by any means. But wow I’d want to see lots of replication and a much, much larger sample size.

LikeLike

Your post unfortunately illustrates primary problems with statistics education.

1. Much of it is built on applied, policy-making premises – are the numbers good enough to justify a given policy. In that context, yes, single studies are not sufficient, and yes, they’ve been employed to bad ends. My lobotomy post shows just how far people can go with such things, and how inappropriate, even bad and irrelevant, a piece of research can be and yet still elevated into policy justification.

This isn’t the case for my current topic at all. There is no policy decision at hand. It’s basic research. The only aim is to add material to the ongoing discussion, and the only way is, one study at a time.

2. Statisticians are obsessed with precision: the way to get their sample variable as close to the inaccessible population value as possible. That’s where the cry of “Sample size! Sample size!” comes from, and the ongoing assumption that a specific measured value is literally supposed to represent a population.

In this study, none of that matters. The precise measured value isn’t the issue, only how it compares with the other measured value. In this case the broad standards of error are a good thing, because when we see the gap between the samples, the distance is, so to speak, overcoming the spray in the data from each sample. You can’t just eyeball an SE and say, “oh, that’s too big.” It’s there for a reason – for the significance to be derived from enough distance to matter.

3. Most many-sample, many-variable studies are fishing expeditions, measuring any damn thing in hopes of a hit, which then gets a paper written around it as if that were the hypothesis test from the start. That’s a good reason to eyeball any “Ooh! Significance! Significance!” claim with suspicion. This study was built correctly, such that only that single comparison – women in the fertile phase, Pill vs. no Pill – addresses the question at hand. This cuts way down on the fact that in a variety of non-consequential comparisons, significance will show up here and there anyway.

It goes back to prior plausibility too: every numerical result in the study accords with expectations if the world works a certain way (women display estrus). You get suspicious when the results do something odd, and that’s when you say, do it again, do It in another lab, up the sample sizes, re-train the technicians … when the results nail the prior plausibility instead, you get convinced.

In this context, p less than 0.016 is no “gee close enough, we’ll publish it ’cause the editor’s my friend” result – it’s landed a solid punch.

I’ve spent decades listening to academics weasel around their statistics in order to preserve a given trajectory or general set of assumptions that are associated with their topic or with their specific lab. This is one study for which none of the above is an excuse. It does exactly what it needs considering what’s being said, and says what it needs to be included.

Science needs a lot more small, well-designed, clear studies like this one. That’s how things get truly discussed, not by Amazing Proof studies, but with a ton of these kicking around and being compared for consistency across a whole bunch of variables. That’s the thing which gets lost in science curricula and as I see it, never really got established in semi-science curricula at all.

LikeLike